"When I meet God, I am going to ask him two questions: Why relativity? And why turbulence? I really believe he will have an answer for the first."

-- Werner Heisenberg

Part I

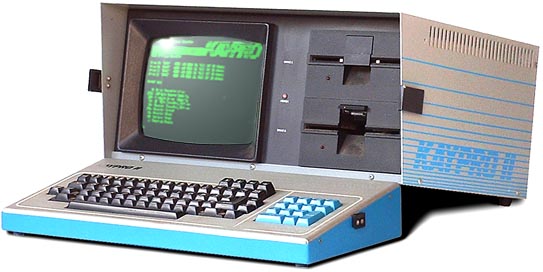

Back when I got my first computer (a used Tandy 1000 with two floppy drives, a 300 BAUD modem, and a whopping 384Kilobytes of RAM -- 128 original + a 256 expansion module -- something like the one above) a dear friend named Chuck insisted I look into chaos theory. It was the mid 80s and Benoit Mandelbrot's theories were all the rage in the artworld. Chuck had written a few little bits of code to emulate a series of chaotic orbital decay events using information he'd found someplace or another, and he found the visual patterns they produced endlessly interesting.

About that time I read a short article in the back of some popular tech magazine describing another kind of chaotic function in a program written in Pascal, so I tried my hand at transcribing it into Basic, which my version of MS DOS supplied for me. The resulting program was laughably primitive, only a few lines long. But it worked. Using the PSet command, it located a point on the screen's x/y axes that represented the values of two variables in a simple equation as determined by the value of a third which was controlled by some function I no longer remember. As the program ran, it drew a line of dots that descended the screen till, at a certain point, the line split, which meant that there were two true values for each of the variables. Then the two lines split. Then all the lines split again. And again.

All this happened in an orderly fashion until it got strange. That's the technical term for what transpired -- the lines my program drew are called attractors, and when they break into apparent disorder, one says that they are strange attractors. Strange they were. Dots proliferated in certain regions of the screen, always descending, but in no pattern that was at first predictable. Eventually another, non-linear structure appeared, a cloud of dots that seemed to coalesce into soft arcing forms that mimicked the arcs if the program's initial lines in a curiously organic way.

Part II

Back in October, the PBS News Hour ran a segment in which Paul Solman interviewed Mandelbrot and Nassim Taleb, the author of The Black Swan, a book about unpredictability and the limits of what we know for certain. About 5:15 into the interview the butterfly effect and the idea of turbulence comes up in their discussion of what's happened and will happen to the enormously complex international financial system. The ripple effects of the implosion of big players like Lehman Brothers and the maiming of bigger ones like AIG are not confined to the values assigned to their shares or to their debt instruments. Ripples are not confined even to one country. In a structure with as many interconnected obligations and mutual dependencies, a structure as unbelievably complex as international finance, they suggested, the effects of a meltdown can be catastrophic. That's the turbulence fear they express.

Look at the smoke from Bogie's cigarrette above (image from Wikipedia). It rises in a smooth ribbon for a bit, spreads, and expands. At first it's coherent, but at a certain point it becomes turbulent, chaotic. Eventually it no longer appears to be a single form; it is no longer even smoke.

Part III

A series of excellent articles by Brady Dennis and Robert O'Harrow, Jr. in the Washington Post describes the events leading up to the AIG disaster in detail. Here are some links: Articles one, two, and three. They are worth reading. The first part tells how three men who worked at the notorious junk bond firm Drexel Burnham Lambert -- Howard Sosin, Randy Rackson, and Barry Goldman -- conceived of new debt instruments that revolutionized the world's finanial markets. they hatched their ideas in 1986, about the time I was noodling with a short program written in Basic to illustrate chaos.

Partnering with AIG, they set up something called AIG Financial Products to offer novel and complex financial instruments. They made themselves and their company enormous amounts of money. And then things got chaotic:

Note two things in the quote above: 1. "no one fully understood;" and 2. "the veneration of computer models."Financial Products unleashed techniques that others on Wall Street rushed to emulate, creating vast, interlocking deals that bound together financial institutions in ways that no one fully understood and contributed to the demise of its parent company as a private enterprise. In the panic of mid-September's crash, the Bush administration said that AIG had grown too intertwined with the global economy to fail and made the extraordinary decision to take over the reeling giant. The bailout stands at $152 billion and counting -- almost 10 times as large as the rescue for the American auto industry.

Many of the most compelling aspects of the economic cataclysm can be seen through the story of AIG and its Financial Products unit: the failure of credit-rating firms, the absence of meaningful federal regulation, the mistaken belief that private contracts did not pose systemic risk, the veneration of computer models and quantitative analysis.

These guys are smart. Sosin is an alumnus of Bell Labs, Rackson of the Wharton School of Management. Goldman holds a PhD in economics. But what was constructed -- the net of international financial obligations -- grew too big and convoluted to comprehend.

The computer models they and their colleagues trusted to guide them through it all suggest a poignant clue to Nassim Taleb's worries about our current situation. Edward Lorenz, the MIT mathematician and meteorologist credited with naming the butterfly effect, made his discovery when he was running an early computer weather model. When he reran one simulation, starting not at the beginning but a little ways into the model, the results were wildly different from his first attempt. The data from the second run were rounded off slightly, and the systems he was modeling are so complex that tiny differences in values -- less than a thousandth place in Lorenz's case -- meant huge differences in output.

A butterfly in Beijing can cause a storm in Texas.

Financial Products' management and the kinds of products they conjured into being changed over the years, but its mathematical and model-based business apparently didn't very much. Tom Savage, a mathematician, replaced Sosin (who left because of conflicts with AIG's management), Joseph Cassano, another Drexel Burnham alumnus, took over the reins. But the rigorous vetting of each transaction continued.

But even as Financial Products experimented, Savage said, he continued to stress the need to minimize risk. "That was one of the things that really marked this company, was the rigor with which it looked at the business of trading. . . . There was an academic rigor to it that very few companies match," he said.

"It was Howard Sosin who said, 'You know, we're not going to do trades that we can't correctly model, value, provide hedges for and account for.' "

The models continued to show that the products they were selling (increasingly credit default swaps -- insurance on third-party debt) were only the tiniest bit risky. It would take the chaos of a world-wide depression to make them go bad.

And then, one mortgage too many failed, so to speak. A mortgage securitized in a bundle of mortgages, which bundle was itself secured by a product sold by Financial Products. A cascade of rising collateral obligations and falling credit ratings ensued.

The butterfly flapped his wings.

Now we taxpayers own AIG. It's cost us $152 billion so far.

But Taleb's fear is that this only the first part of the ensuing storm. Turbulence and chaos are like that. What will come of AIG's troubles is yet to be seen.