Okay, Alice Waters makes me tired. She’s domineering, precious and the product of much privilege – privilege she appears incapable of unlearning. In Thomas McNamee’s Alice Waters biography she is quoted regarding the end of her marriage to the effect that she knew her ex was unhappy and felt she made all the big decisions in their lives without his input, but she’d always thought they could work it out. (My paraphrase is probably harsher than her actual words, but the point struck me pretty hard.)

Yet I’m not ready to toss out the Waters' Edible Schoolyard idea like Caitlin Flanagan. And I can not equate gardening with field hand labor, as Flanagan does in her Atlantic article. There is much to learn from the experience of gardening, and it doesn’t necessarily conflict with educational achievements in math and language arts. Flanagan’s piece doesn’t mention that Waters is a trained Montessori teacher when she writes of “her decision in the 1990s to expand her horizons into the field of public-school education.” Regardless of one’s estimation of the Montessori method – I’m agnostic on the subject – Waters is not a dilettante in educational matters.

I know about Waters’ Montessori training because, like Flanagan, I read McNamee’s biography. Presumably Flanagan does, too. And yet she writes that Waters is “someone whose brilliant cookery and laudable goals may not be the best qualifications for designing academic curricula for the public schools.” Cherry pick facts much?

Much of Flanagan’s point revolves around the issue of class. After introducing us to a farm worker’s son who goes to school only to pick lettuce in the hot sun, she writes : “[Waters’] goal is that children might become ‘eco-gastronomes’ and discover ‘how food grows’—a lesson, if ever there was one, that our farm worker’s son might have learned at his father’s knee—leaving the Emerson and Euclid to the professionals over at the schoolhouse." That the farm worker’s son has knowledge on the topic is an interesting point to my mind, and not the least because his knowledge empowers him to own and teach the lesson. He is one sort of expert in the field of study. Leaving geometry and American Transcendentalism to others in favor of lettuce-picking, however, is surely not at issue because there is a garden in the schoolyard. The two are in no way incompatible.

I do not advocate accepting low academic achievement while teaching gardening in schools. That would be just plain stupid. But how much time do the children spend gardening in the project? Ninety minutes a week, according to Flanagan. And then they work in academic classrooms on related projects, which Flanagan believes interferes with mastering the basics of math, science and language arts. I don’t know if this is so, but if it is, it must be improved. Checking the Edible Schoolyard Web site showed me a couple of sample middle school math problems related to the garden and cooking: solving for x and y in a problem that asks the student to double a recipe, and building a model of a garden structure that has these interrelated polygons in these proportions. I’d be interested to see how they stack up against lessons in other 7th and 8th grade math curricula. If they are not up to snuff, then they should be improved. That they refer to the general topic of gardening and food is not itself reason to reject them, however.

I participated in establishing a community garden last year, and the community part of the enterprise amazed me. People who otherwise would never have met collaborated with one another. An artist became the friend of a plumber and a county commissioner. A Glen Beck fan worked along side Obama voters. A Church of the Nazarene preacher assisted non-believers and even a few Hindus make raised beds and plant vegetables. An agricultural science professor and a photographer spread mulch and composted manure.

All these diverse individuals came together because they were inspired by a common project. In one sense any common project – fire house, art gallery, or public restroom – would have done the trick. But that the task involved raising food added meaning to the work beyond a simple common purpose.

Food is important.

Beyond providing mere fuel, food is a part of the external world which has been selected according to custom and tradition, purified by fire and taken into our bodies. What we eat is subject to a symbolic, even spiritual dimension. Not for nothing do Christians profess communion though the symbolic act of eating and drinking. Not for nothing is Passover observed with a meal. Not for nothing is Ramadan a time of fasting. Not for nothing are there dietary laws associated with many great religions.

Alice Waters can be irritatingly foodie-righteous. Anthony Bourdain once compared her to the Khmer Rouge because of her intractability. But I believe she has a point when she asserts out that many of us have lost a meaningful sense of belonging to the earth because of the ways we approach food: industrialized, anonymous, processed beyond recognition. In this she is not alone. We are witnessing a cultural shift in America with respect to food and our relation to it. Alice Waters is only part of the change we are experiencing. Michael Pollan’s books on the subject echo and elaborate on many of her ideas. The connection between processed food and obesity has been researched and documented in physical anthropologist Richard Wrangham’s excellent book “Catching Fire: How Cooking Made us Human.” Michelle Obama’s White House Food Initiative is also part of our changing system of beliefs on the topic.

What I have called a cultural shift Flanagan terms “Food Hysteria.” I assume the difference boils down to duration as much as anything. If my cultural shift jumps the shark next year, it’s Flanagan’s “Hysteria.” It is entirely likely that I am wrong and that I'm merely a faddist, but I am glad we built our community garden. And I’d like to see an edible schoolyard in my little town.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Friday, November 6, 2009

Connecting the dots; counting the beans

One of the ugly things that precipitated the current financial mess involved large financial institutions holding assets that turned out to be a lot less valuable than they wanted them to be when they had to state what stuff they held was worth against what they were obliged to pay out. Specifically big finance found itself holding a lot of paper last year that should by rights be worth billions, but turned out to be illiquid in the skeptical market that followed the credit meltdown. So a bank with a buttload of collateralized mortgage obligations in its portfolio that they valued at a buttload of bucks had to let the world know every once and a while that their buttloads were basically half assed. Or worse. This made them less able to borrow money themselves and so they began to contract. Stating the market value of their holdings was integral to the current meltdown because a lot of their holdings were considerably less valuable than they'd thought. But the rules said they had to tell the truth.

I've blogged about this before -- over a year ago, in fact -- but some bad ideas just won't go away. Now the money boys want to put the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the folks charged with setting standards for honesty in accounting, under an oversight committee that will have leeway in calling for honesty in assessing the value of "distressed" holding during times of extraordinary financial conditions. There's to be normal honesty and another -- abnormal -- sort of honesty, when conditions mandate.

Last night at a gallery in Dallas, I spoke with a woman who, informed that the painting we were admiring was on sale for $95,000, asked why it cost so much. My answer was that was what the market would bear. It is worth what can reasonably be expected, given prior sales and the condition of the market so far as the artist and his dealer can assess it. Under those conditions, the painting was offered at that price.

Will it sell? Hell, I don't know. I own a six-year-old car. It is available for a price. If I set the price too high, it won't sell. Price it low enough, however, and I make a sale. Will that painting sell? It will if $95K is the right price.

The same is true for a CMO. Its value is what you can sell it for. A financial institution with illiquid assets on its books can not arbitrarily assess the value of its holdings apart from what they will sell for. What does it cost to buy it? Well, that's what it is worth. This is what is called mark-to-market accounting.

And yet it would appear there are arguments for another valuation system -- one based on the wishful thinking of bankers, not their much loved market. There is a move underfoot to move FASB into another realm, a realm devoted to loosening standards of valuation when "systemic risk" is abroad in the land and children are routinely devoured by wild things. The story is discussed here.

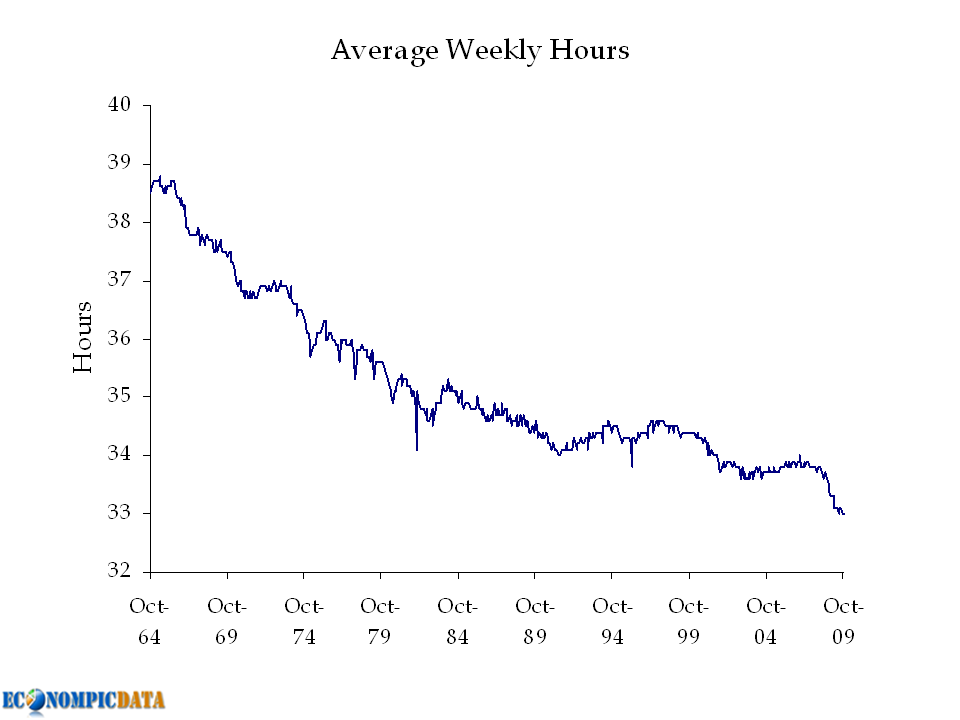

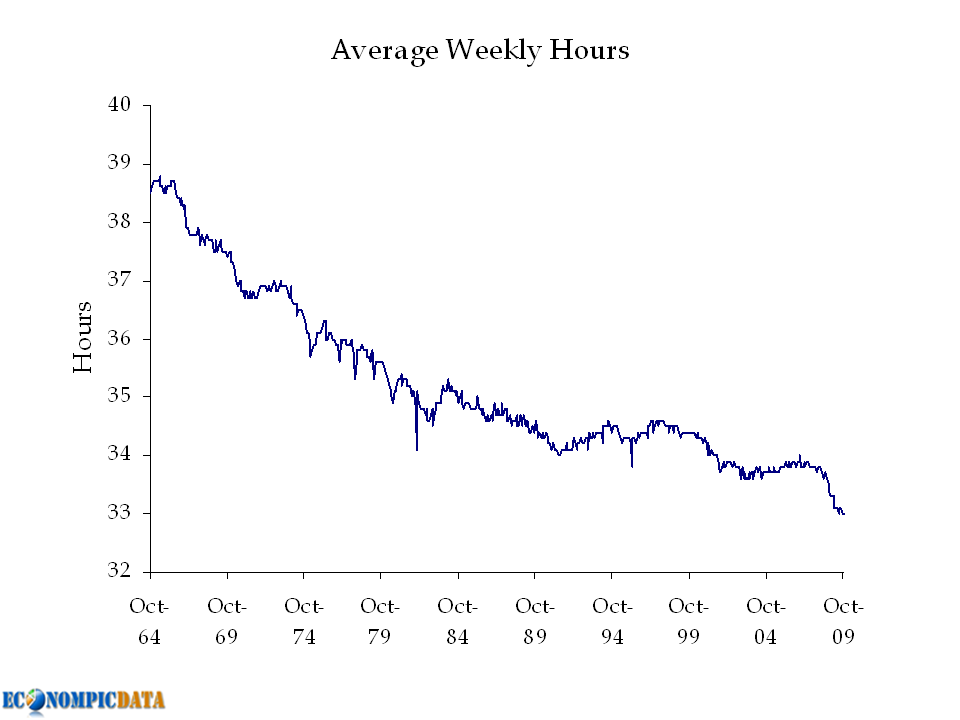

Meanwhile, check this:

(Image from Ritholtz)

(Image from Ritholtz)

The people of our nation are not working. This is because of a financial crisis. The crisis was caused by inadequately comprehending the values of assorted financial instruments and consequent recklessness in trading them.

Two thirds of all the economic activity in America is consumer spending. Jobless folks are way less likely to spend than their employed counterparts. And even employed folks who fear unemployment are less likely to buy stuff.

Loosen accounting rules? Sure. That's a great idea.

I've blogged about this before -- over a year ago, in fact -- but some bad ideas just won't go away. Now the money boys want to put the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the folks charged with setting standards for honesty in accounting, under an oversight committee that will have leeway in calling for honesty in assessing the value of "distressed" holding during times of extraordinary financial conditions. There's to be normal honesty and another -- abnormal -- sort of honesty, when conditions mandate.

Last night at a gallery in Dallas, I spoke with a woman who, informed that the painting we were admiring was on sale for $95,000, asked why it cost so much. My answer was that was what the market would bear. It is worth what can reasonably be expected, given prior sales and the condition of the market so far as the artist and his dealer can assess it. Under those conditions, the painting was offered at that price.

Will it sell? Hell, I don't know. I own a six-year-old car. It is available for a price. If I set the price too high, it won't sell. Price it low enough, however, and I make a sale. Will that painting sell? It will if $95K is the right price.

The same is true for a CMO. Its value is what you can sell it for. A financial institution with illiquid assets on its books can not arbitrarily assess the value of its holdings apart from what they will sell for. What does it cost to buy it? Well, that's what it is worth. This is what is called mark-to-market accounting.

And yet it would appear there are arguments for another valuation system -- one based on the wishful thinking of bankers, not their much loved market. There is a move underfoot to move FASB into another realm, a realm devoted to loosening standards of valuation when "systemic risk" is abroad in the land and children are routinely devoured by wild things. The story is discussed here.

Meanwhile, check this:

(Image from Ritholtz)

(Image from Ritholtz)The people of our nation are not working. This is because of a financial crisis. The crisis was caused by inadequately comprehending the values of assorted financial instruments and consequent recklessness in trading them.

Two thirds of all the economic activity in America is consumer spending. Jobless folks are way less likely to spend than their employed counterparts. And even employed folks who fear unemployment are less likely to buy stuff.

Loosen accounting rules? Sure. That's a great idea.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Dallas gallery hopping

I prowled the scene this afternoon. Here's what I saw and thought.

At Barry Whistler Gallery, Lawrence Lee is still up and shining with some of the most elegant lines I've gazed upon since I first got acquainted with Fragonard's tree drawings back in the days of Bush I. Lee mines old racist depictions of African Americans and his supple imagination to produce some truly witty narrative-based graphite and ink and tea and who knows what drawings of crazy-assed tall tales that probably make sense only to him. So why tell the stories? Because they look great. And there's always that astonishing line of his.

The image above is from Lee's show at the now-defunct Clementine Gallery in Chelsea a couple of years ago. He's getting better.

The image above is from Lee's show at the now-defunct Clementine Gallery in Chelsea a couple of years ago. He's getting better.

Road Agent may or may not be defunct also. It still has the "Installation in Progress" sign on the door from last month. As I understand it, gallery owner Christina Rees has accepted a position as director at TCU's off-campus exhibition space over in Fort Worth.

Fort Worth 1, Dallas 0.

Dunn and Brown is offering Dale Chihuly glass stuff to discerning folks in the Metroplex. Why? I don't know. Maybe the bills are coming due. Still they had a kickass small group show in their "project" space with works by Trenton Hancock (whom I love and not just because he once speculated that everybody's soul looks like a pre-teen Caucasian girl), Jeff Elrod, Erick Swinson, Vernon Fisher, etc.

Swinson's savagely trompe l'oeil sculptures of a pre-hominid creature and a stag shaking off the bleeding"velvet" from its new antlers take the Halloween prize for amazingness and craft.

Down in the Design district, Conduit offered Michael Tole and Joe Mancuso. Too many flowers on one picture plane (yes, that's the point) and painstaking renderings of Chinese decor. Cool, but why? I can't say. Somebody tell me.

I tried to see the new stuff by Dornith Doherty at Holly Johnson, but the place was temporarily shut when I dropped by. Should have called first, I guess.

Over at Marty Walker, I caught a sneak peek of William Lamson's new work, and it was a pleasure. Building on his videos from last year, he set up several ad hoc machines designed to use wind and waves to make drawings during his recent tour of South America. The Chilean coast wave works were delicate and appropriately atmospheric. Others were bolder and more aggressively "expressionistic." Whatever that might mean when a kite is doing the expressing.

Above: William Lamson, Kite Drawing Jan. 31, 2009. 740-915 PM. Colonia Valdense, Uruguay.

The Goss Michael Foundation offered a small Mark Quinn survey. He's the dude who cast his own head in his own blood. If he makes it, he means it. Got it?

Quinn's Mother and Child (Alison and Parys), 2008, a marble sculpture of a nude woman and her baby, was an extraordinary thing to behold. Handsome and at peace with her body, Alison was born without arms and with improperly formed legs. Gallery literature quotes him as saying "She's very beautiful, she just looks different."

He's right.

At Barry Whistler Gallery, Lawrence Lee is still up and shining with some of the most elegant lines I've gazed upon since I first got acquainted with Fragonard's tree drawings back in the days of Bush I. Lee mines old racist depictions of African Americans and his supple imagination to produce some truly witty narrative-based graphite and ink and tea and who knows what drawings of crazy-assed tall tales that probably make sense only to him. So why tell the stories? Because they look great. And there's always that astonishing line of his.

The image above is from Lee's show at the now-defunct Clementine Gallery in Chelsea a couple of years ago. He's getting better.

The image above is from Lee's show at the now-defunct Clementine Gallery in Chelsea a couple of years ago. He's getting better.Road Agent may or may not be defunct also. It still has the "Installation in Progress" sign on the door from last month. As I understand it, gallery owner Christina Rees has accepted a position as director at TCU's off-campus exhibition space over in Fort Worth.

Fort Worth 1, Dallas 0.

Dunn and Brown is offering Dale Chihuly glass stuff to discerning folks in the Metroplex. Why? I don't know. Maybe the bills are coming due. Still they had a kickass small group show in their "project" space with works by Trenton Hancock (whom I love and not just because he once speculated that everybody's soul looks like a pre-teen Caucasian girl), Jeff Elrod, Erick Swinson, Vernon Fisher, etc.

Swinson's savagely trompe l'oeil sculptures of a pre-hominid creature and a stag shaking off the bleeding"velvet" from its new antlers take the Halloween prize for amazingness and craft.

Down in the Design district, Conduit offered Michael Tole and Joe Mancuso. Too many flowers on one picture plane (yes, that's the point) and painstaking renderings of Chinese decor. Cool, but why? I can't say. Somebody tell me.

I tried to see the new stuff by Dornith Doherty at Holly Johnson, but the place was temporarily shut when I dropped by. Should have called first, I guess.

Over at Marty Walker, I caught a sneak peek of William Lamson's new work, and it was a pleasure. Building on his videos from last year, he set up several ad hoc machines designed to use wind and waves to make drawings during his recent tour of South America. The Chilean coast wave works were delicate and appropriately atmospheric. Others were bolder and more aggressively "expressionistic." Whatever that might mean when a kite is doing the expressing.

Above: William Lamson, Kite Drawing Jan. 31, 2009. 740-915 PM. Colonia Valdense, Uruguay.

The Goss Michael Foundation offered a small Mark Quinn survey. He's the dude who cast his own head in his own blood. If he makes it, he means it. Got it?

Quinn's Mother and Child (Alison and Parys), 2008, a marble sculpture of a nude woman and her baby, was an extraordinary thing to behold. Handsome and at peace with her body, Alison was born without arms and with improperly formed legs. Gallery literature quotes him as saying "She's very beautiful, she just looks different."

He's right.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

A food show

My piece is up and running at Project Gallery in Wichita, and I'm quite satisfied with it. Here's a quick, down-and-dirty edit of some installation shots.

The opening was Friday night. Saturday, the gallery organized a potluck dinner. Everybody brought something to share. My wife and I brought some homemade, locally sourced food: home cured bacon, home cured pastrami, a salad of purple hull peas we grew in the community garden, some home canned okra pickles, and some home canned pickled watermelon rind.

I fried the bacon for about the first half hour of the event, feeling a little bit like Rirkrit Tiravanija, but sillier and more bacon-y.

It was a lovely weekend.

The opening was Friday night. Saturday, the gallery organized a potluck dinner. Everybody brought something to share. My wife and I brought some homemade, locally sourced food: home cured bacon, home cured pastrami, a salad of purple hull peas we grew in the community garden, some home canned okra pickles, and some home canned pickled watermelon rind.

I fried the bacon for about the first half hour of the event, feeling a little bit like Rirkrit Tiravanija, but sillier and more bacon-y.

It was a lovely weekend.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Cow Hill tonight

(Image from Keri Oldham's Web site)

(Image from Keri Oldham's Web site)I'm just back in from the front porch, the coyotes are howling out on the prairie and the street out front is damp. It shines under the lamps.

Last night we attended an opening for Peter Barrickman and Keri Oldham at Centraltrak in Dallas. Keri used to be a gallery manager at the now defunct And/Or Gallery. I reviewed a show they had last spring. Keri's watercolors are endearingly creepy, a blend of fashion illustration and automatic drawing where somatotype and psyche meet on an uncomfortable picture plane.

Barrickman's work is all over the map, but the fractured and squashed pictorial space of a landscape and idiosyncratic expression would seem to be his interest. Not surprisingly, collage enters into the mix often. Collage can do that to space.

At present, I'm imagining a review of Amy Blakemore's show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The magazine's deadline is Tuesday, and it's not yet written. Tonight I'm thinking of remembering the times I was disabused of comforting, but false, notions of how the world is. Amy's pictures are like that. Hard as stone and sweetly, achingly melancholy. Here's a beautiful picture. You loved him. He's dead. But still you love him. Let this picture's beauty comfort your loss. It's not love, but beauty is at least something.

Monday, August 31, 2009

Houston trip -- two kinds of strangeness

My wife and drove to Houston last weekend to see the Amy Blakemore show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and to spend a little time away from this tiny town.

Blakemore's photos are powerful evocations of disillusionment and fading memories. Some of them are evocative of the emotional content in James Joyce's short story "Araby" in their sense of melancholy epiphany: "I thought it would be better, more than this..." Other times, her blurred and granular exposures suggest tilt shift digital photo processing. Always they are strange and haunting.

(Images via Inman Gallery)

Before we left for home this morning, we visited a Salvation Army thrift store on Washington Ave. in Houston because of an article I'd read in the NY Times about some works said to be by Salvador Dali that are up for sale there. Opinions vary concerning their authenticity, naturally, but I've seen them in situ. The drawing, sculpture, and prints are indeed on display in a glass case in the thrift store.

I took some pictures of the display, and my wife got a real bargain on a light sweater and some tops.

Friday, August 28, 2009

Ted Kennedy

Here's a bit from an admittedly liberal blog. When he attended the funeral of murdered Israeli PM Rabin, Ted Kennedy quietly placed earth from the graves of his brothers on the grave of the slain peacemaker. His brothers were known to us all as political figures which we associated with certain ideals, but he knew them as his brothers. Blood kin. The dirt was not just dirt. It meant something, if only privately

Ted Kennedy's sins and transgressions were very public. His position of privilege got him out of some really bad situations that none of us could have hoped to escape, and these situations were largely of his own making. These facts offend the small d democrats of America. We hate class privilege. It isn't right. Well it isn't.

And yet he did accomplish some really good things in his many years in the senate. At least I think much of what he did was good. He was a major influence on the laws of our country, shaping them in ways that served to uplift and make better the lives of people who were decidedly not privileged. Here's some of what he did: Title IX (gender equality in college athletics), the ADA, race-blind immigration legislation, bilingual education, Meals on Wheels, the National Commission on the Protection of Human Subjects (in med/sci experiments), stopping military aid to the fascist Pinochet regime in Chile, education for children with disabilities, expanding the civil rights act to protect persons with disabilities, the Civil Rights for Institutionalized Persons Act, the Refugee Act of 1980 (asylum for persecuted persons), Employment Opportunities for Disabled Americans Act, the National Military Child Act, Civil Rights Act of 1991, Americorps, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, voted no on war with Iraq (one of 23 senators who did so).

Most of what he accomplished, he accomplished after that evil night at Chappaquiddick when Mary Jo Kopechne died. It is as though he had begun as the callow, drunken libertine his enemies call him -- a selfish irresponsible glutton who was rich enough and Kennedy enough to buy his way out of anything with money and social connections. But then something else emerged, something with a will and a capacity to make our nation better. In working to make America better, I think, he may have also worked to make himself better.

I am fully aware that some amongst us do not share my belief that he made our country better, and that is what it is. We will certainly disagree about many other things. It was always so. But the Americorps program has had a very real and beneficial effect on some of the little towns that dot this run-down portion of NE Texas. I've seen it. And allowing people from India and China and Jordan and Mexico to immigrate legally to the US the same as people from Western Europe has truly benefited this nation. Look what's happened to our national cuisine alone. I mean jeez!

Ted Kennedy did that for us. And he came to embody a certain attitude -- love it or hate it or whatever -- which may have died with him. He stood for something. He meant something.

Add to that the fact that he was a Kennedy. He was the son of Joe Kennedy, ambassador and alleged bootlegger millionaire. He was brother to Joe, Jr who died on an Air Corps mission in WWII, and brother to Jack who skippered PT 109 and survived to become a senator and later President of a Camelot White House before his murder. He was brother to Robert, murdered on the night of his triumphal victory in the 1968 California primary -- that terrible year of political murders. He was their blood kin, of their generation. My parents' generation.

And it passed with him.

I recall the November day in 1963 when John Kennedy as killed. We lived in a Dallas suburb at the time. I remember my mother sobbing on her bed. I remember not knowing what to do because I was still just a boy. And now the question arises. Why did she cry? She didn't know him. He was unrelated to her. He was a stranger. He was a glamorous, powerful man with a glamorous wife who lived a life so disconnected from the suburban reality of my mother's existence that they may as well have been separated by an ocean. But she sobbed that November afternoon for what had happened to him. And for what had happened to us. He meant something to us.

I once wrote a review of a show of Warhol's Jackie paintings which was presented in the building Lee Harvey Oswald used for his sniper's perch that awful day. My editor cut a line I'd written about our all being widowed after the killing of our President. But it was the memory of my mother sobbing that led me to write it. How can you explain that to an editor?

When Jackie died years later my mother bought a ticket to Europe. She had to get away even though she was retired and not flush with disposable cash. "That woman was too young to die" she explained. Jackie meant something. True or false, she meant something.

Ted wasn't John. Everybody knows that. He wasn't Bobby either. But he was ours. He was a Kennedy. And he was the last of them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)